By Chris Eboch

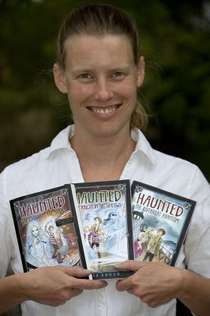

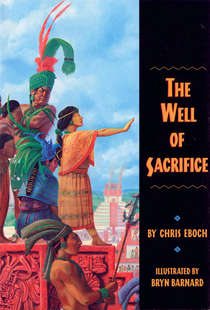

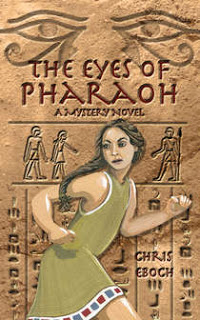

After a dozen books in print, I like to think I’ve learned a few things. After all, I’ve written historical fiction (The Eyes of Pharaoh, a mystery set in ancient Egypt, and The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan adventure), original paperback series (the Haunted series, which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs), and various types of work for hire, including fictionalized biographies and a mystery about a certain famous girl sleuth.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean the next book is always easy. Every novel has its own challenges and flaws. I tend to be analytical, and I have years of experience as a teacher through the Institute of Children’s Literature and as a freelance editor. So I’m always looking for clear, logical techniques to improve my writing, and that of my students. A couple of years ago I picked up a writing book that suggested you make an outline of your finished manuscript. My mind jumped ahead, seeing the possibilities. This could be a great tool for analyzing your work!

But the author didn’t do what I expected. She had some good points to make, but I thought she was missing an opportunity. I developed a system of my own, testing it with my manuscripts and in a class I taught, pulling in suggestions from other articles, editing and refining. And I came up with what I now call the Plot Outline Exercise.

Briefly, you make an outline of your finished manuscript, noting the main action and any subplots in each chapter, along with the level of conflict, the primary emotions, and the chapter length. Then you analyze your plot. I divide the analysis into sections for Conflict, Tension, Main Character, Subplots and Secondary Characters, Theme, and Fine Tuning, with over 40 bullet points. Here are the opening three, from Conflict, as examples:

· Put a check mark by the line if there is conflict in that chapter. For chapters where there is no conflict, can you cut those, interweave with other chapters, or add new conflict? The conflict can be physical danger, emotional stress, or both, so long as the main character (MC) is facing a challenge.

· Where do we learn what the main conflict is? Could it be sooner? Is there some form of conflict at the beginning, even if it is not the main conflict? Does it at least relate to the main conflict? The inciting incident—the problem that gets the story going—should happen as soon as possible, but not until the moment is ripe. The reader must have enough understanding of the character and situation to make the incident meaningful. Too soon, and the reader is confused. Too late, and the reader gets bored first.

· Where do we learn the stakes? What are they? Do you have positive stakes (what the MC will get if he succeeds), negative stakes (what the MC will suffer if he fails), or best of all, both? Could the penalty for failure be worse? Your MC should not be able to walk away without penalty.

As you work your way through the questions, you make notes on your outline about changes you’ll need to make to the manuscript. (I think it’s important that you study the overall manuscript and make notes first, rather than starting to fiddle with problems as you find them. You don’t want to waste time editing a chapter that you later decide needs to be cut.)

As an example, here is an outline of the opening scenes of my unpublished middle grade novel, The Mountain, featuring a 12-year-old boy who runs into mysterious people while hiking in the woods.

Chapter 1, 12 pages: Jesse plans a fishing trip while dealing with family secrets. Conflict—yes, related to family. Emotions—Jesse is angry and resentful. Subplot—family secrets.

Notes: Delete opening scene and start the next day when Jesse is ready to leave. Bring his father into the scene, showing the distance between them. Trim chapter to get Jesse out of the house and into the woods quickly—move scene with Becca to later in the book.

Chapter 2, seven pages: Jesse goes hiking, follows tracks, and meets a woman in the woods. Conflict—tension, but no major conflict. Emotions—confidence, then curiosity.

Notes: Cut scenery to get to action sooner. Have Jesse briefly get annoyed at family secrets while hiking. Increase conflict by having him notice blood on the trail.

Outlining the book this way helped me take a step back and see problems. I had conflict in the first scene, but it didn’t relate to the main problem—the mystery in the woods. I needed to get Jesse into the woods more quickly. Then I had two chapters, one of them very long, with no major conflict. Since this is a suspense novel, I needed to increase the conflict, make the strangers more mysterious early on, and pick up the pace, deleting some of the description.

I also noticed that I dropped the family secrets subplot through much of the book, because Jesse is not at home most of the time. I needed to find ways to include that, if only by having him think about it.

The Plot Outline Exercise is flexible, and you can even use it at the outlining stage. To make the system more useful for others, I combined it into a book with essays covering specific techniques that come up in the Exercise questions, such as developing strong first chapters, writing vivid scenes, and using cliffhanger chapter endings.

Some of these essays I expanded from articles I’d previously written for Children’s Writer or Writers Digest. I also invited guest authors from a variety of genres, including romance, mystery, and fantasy, to share their insights. I cross-referenced the essays with the bullet points in the Plot Outline Exercise, so once users identified the problem, they could learn more about how to solve it. All this information became my book, Advanced Plotting.

If you’d like to learn more, stop by my blog, Write Like a Pro! where I’ve been posting a series of excerpts from Advanced Plotting. You can download the complete Plot Outline Exercise HERE (scroll down on the left), or you can buy the book in paperback or as an e-book from Amazon

Chris teaches through the Institute of Children’s Literature and is the New Mexico Regional Advisor forthe Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. She has her MA degree in Professional Writing and Publishing from Emerson College in Boston, as well as a BFA in Photography from Rhode Island School of Design. She has worked as an editor and writer for magazines. She has taught Fiction Writing and has led dozens of workshops for children and adults.

Learn more about Chris and read excerpts of her work at www.chriseboch.com (for children’s books) or www.krisbock.com (for adult romantic suspense written under the name Kris Bock) or see her Amazon page at http://www.amazon.com/Chris-Eboch/e/B001JS25VE/.